TLDR; There’s now an MQTT Client implementation written in UnrealScript

I’ve been doing a bit of stuff in UnrealScript recently, and reacquainting myself with it.

Something I’ve always been aware of, but have never really looked at in much detail, is that it has an actual TCP client you can extend to implement whatever remote communications protocol you’d like.

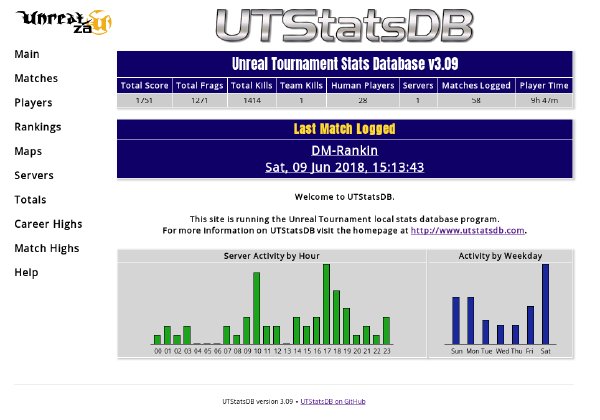

For whatever reason MQTT popped up as my candidate to play with, with the thought that you’d be able to publish in-game events to some topics and build interesting things with (the first thing that came to mind was a match stats collection service which doesn’t rely on the traditional process of log scraping), in addition to allowing in-game functionality to respond to incoming events by way of topic subscriptions. And being something targeted at supporting very simple IoT devices, the protocol should be fairly easy to work with.

Thus, we jump into the comprehensive but sometimes strangely documented MQTT version 5.0 protocol documentation to find out how it works. It is indeed fairly straight forward.

Now to find out how the Unreal Engine 1 TcpLink class works. Keeping in mind

this was implemented in the late 90s, data was smaller, data structures were

generally less complex, and not everything was networked.

Firstly, opening a connection is a bit of a process.

- Request resolution of a hostname by

Resolve(hostname); - An event,

Resolved(ipAddr)will fire, with the resolved IP address (integer representation) - Then, you manually bind the client’s ephemeral port with, a simple

BindPort- this immediately returns a bound port number - If your port was bound, you can call

Open(ipAddr) - An event,

Opened()will fire when the connection is established, and you may now send and receive data.

So slightly more manual than a higher level implementation in most modern languages, but when you consider the engine is single-threaded, it’s quite a reasonable process to get around blocking on network I/O.

Sending data is fairly simple, via the SendBinary(count, bytes[255) function.

If you have more than 255 bytes of data to send, it’s a simple matter of

re-filling the 255 byte array and repeating, until you’re done.

Initially, I tried to use the ReceivedBinary(count, bytes[255]) event for

processing inbound data, but due to a known engine bug, this only serves up

garbage data, so we’re left relying on ReadBinary(count, bytes[255]) which

similar to sending, you can call multiple times on a re-usable buffer until the

function returns 0 bytes read.

To make working with data using these processes a bit easier, I implemented a

ByteBuffer class, modelled exactly after Java NIO’s

ByteBuffer.

I feel allocating a re-usable fixed size buffer array which can be

compact()ed, followed by a series of put(bytes[255]), and an eventual

flip() to allow reading is both performant and simple to reason about.

Implementing this ByteBuffer class also gave me a better understanding of the

Java ByteBuffer in the process, even though I’ve been using it for years, it

helps to reinforce understanding of some of the implementation details.

So, using this process of connecting, filling buffers, parsing them according to the specification, sending responses and so on gives us a nice suite of functionality within the client itself. We also want to support custom subscribers which allow other code and mods to receive events from MQTT subscriptions.

UnrealScript of course does not have the concept of Interfaces, but does

support inheritance, so by extending MQTTSubscriber, custom code can do what

it needs to, using the receivedMessage(topic, message) on subclasses of that

class.

UnrealScript also provides a very neat child/owner relationship between spawned

Actors, and so we’re making use of this to attach subscribers to the MQTT

Client. Two standard events the MQTTClient makes use of for this are

GainedChild(child) and LostChild(child), which notify the client when a

subscriber has been spawned as a child of the client. On gaining a child, the

client can automatically establish a subscription for the subscriber’s topic,

so it can start receiving those messages. Similarly, when it loses a child, the

client can automatically clean up any related topic subscriptions.

This process allows neat life-cycle management of both the subscriber classes themselves, as well as the actual server-side topic subscription, by leveraging built-in language/system functionality.

Overall, I’m happy with the end result, both in final utility of the

implementation, and it’s usability for users of the classes involved. It was

also pretty educational and enlightening to see how this old single-threaded

engine deals with network connectivity, and the process of building the

ByteBuffer also helped reinforce my understanding of Java’s implementation

as well.

Now that we have

Now that we have  So far, we’ve covered the basics of

So far, we’ve covered the basics of  In part 1, we went over the basics of

In part 1, we went over the basics of

I’ve been meaning to

do some posts on setting up a Java build process using Apache’s

I’ve been meaning to

do some posts on setting up a Java build process using Apache’s

Recently, I’ve made the switch from KDE being my preferred Linux desktop

environment/window manager, to

Recently, I’ve made the switch from KDE being my preferred Linux desktop

environment/window manager, to